Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. Emerita Professor, Scholar, Translator … aspiring Watercolorist

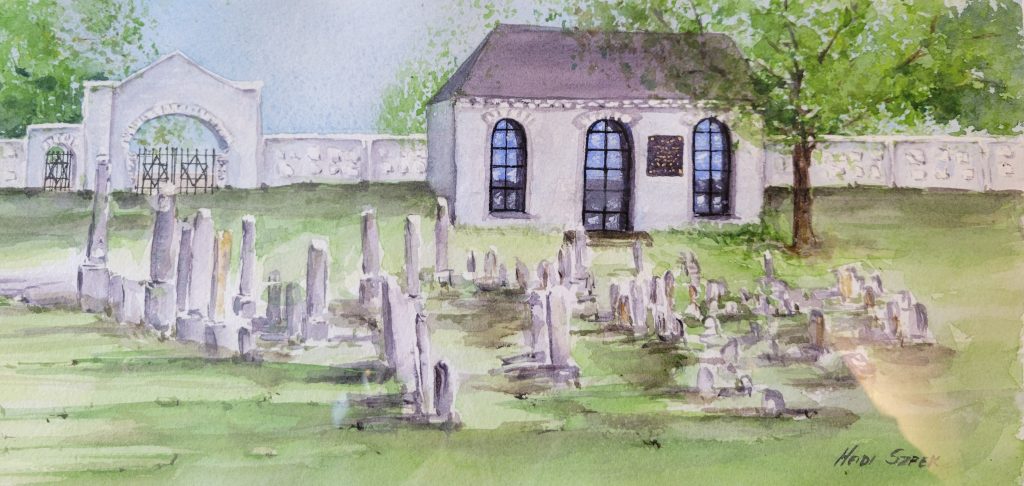

As a professor and scholar of Hebrew and Semitic languages, a translator of the Jewish epitaph, a board member of the NGO Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project, more recently, I’ve taken up a new profession as an aspiring watercolorist. In 2017, I painted a simple panorama of the main entrance to Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, present-day Poland, a cemetery that I have researched since 2004 and engaged in its restoration since 2010. While my vanishing point in this painting needs a little more work, the result still transports me to this cemetery – the arch of its entrance, the Aramaic prayer above that entrance, the cemetery wall that seems to stretch forever down ul. Wschodnia. I can almost feel the warmth of the many August days engaged in work here, the scent of grass and the earth … with recollection of those eternally at rest and those past and present engaged in this cemetery’s renewal. With this first painting, I realized that art can be used as a tool to preserve the past, record the present and imagine a future that reconnects to that past.

Amidst the pandemic lockdown, watercolor became an escape from the luxury prison of my home. Working my way through the Bialystok Conservator’s 1985 report on Bagnowka, I came across a photo that revealed this cemetery once had a pedestrian entrance, adjoining the main processional one. Its presence parallels those at the nearby Catholic and Russian Orthodox cemeteries. This photo also indicates that the entrance and walls may not have been plastered and whitewashed as they are today, and the top of the cemetery walls were peaked perhaps to deter vandalism. These features are likewise present on nearby Christian cemeteries. In the 1990s, Bagnowka’s walls were whitewashed, and, for some reason, the pedestrian entrance removed. In my watercolor, I restored the pedestrian entrance, incorporating the arches’ brick detail, yet retaining the contemporary plastered and painted walls. While we have yet to discover the original design of the cemetery’s wrought iron gates, the design in this painting is inspired by a common style found throughout the Podlasie for Jewish cemeteries and recorded in a 1990 photo of the cemetery.

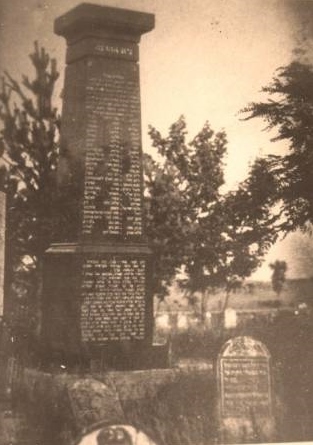

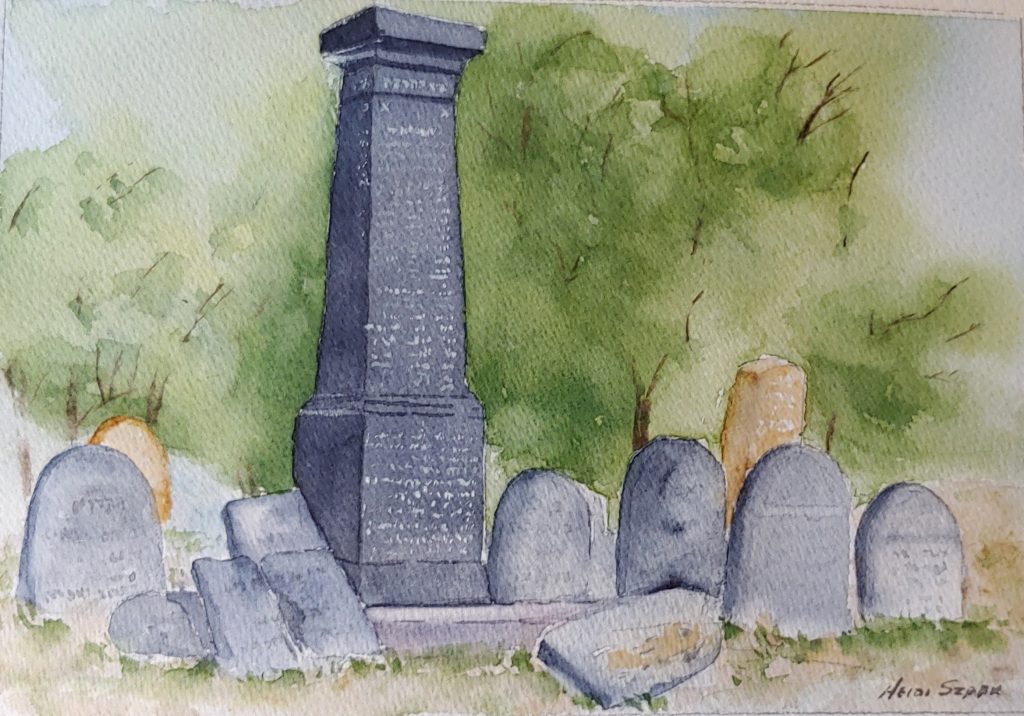

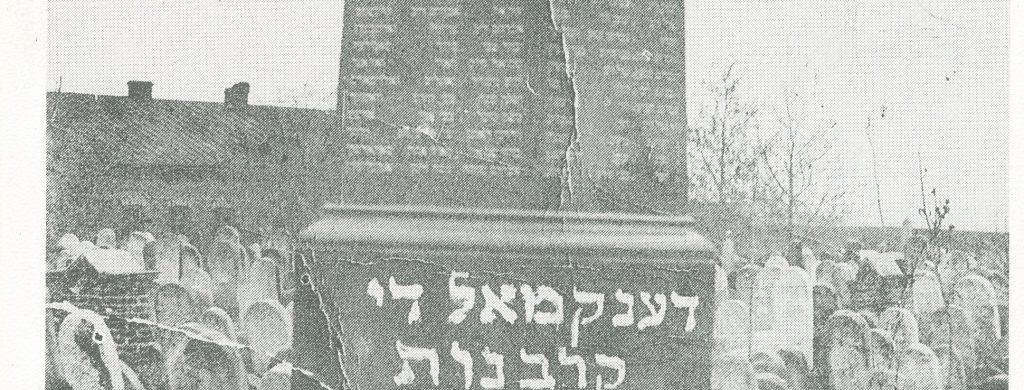

In 2014, in conjunction with Bialystok’s Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej Polska-Izrael, I guided international volunteers of Aktion Süchnezeichen Friedendienste in restoration efforts on the Memorial Complex on Bagnowka Cemetery. At its center is the Black Obelisk, which first and foremost remembers the 1906 Pogrom in Bialystok. We made great progress that year in resetting memorial tombstones that stood before the pillar’s main façade. In subsequent years, however, I learned much more about this pillar, especially that it does not stand in its original location. Vandalized in 1981, it could not be reset in situ and the narrow upper register, engraved with the words “Valley of Slaughter” in Hebrew on each façade, was damaged beyond repair and is now absent. As we continue to restore the current Memorial Complex and make plans to restore what remains of the pillar’s original setting, we also plan to properly restore the pillar. An improper restoration effort in 1994 left paint peeling, with the pillar standing on a weak foundation. There are knicks and occasional cracks on its surface, evidence of the trauma this pillar endured. In my opinion, these should remain if they do not upset the integrity of the pillar. In my watercolor rendition, the upper register has been restored. Though a subtle change, perhaps unnoticed by many, its presence, however, is critical to the language of this stone. On each side, these words from the prophet Jeremiah instantaneously provoke the visitor to consider the circumstances that necessitated this monument. Was Bialystok once a “Valley of Slaughter”?

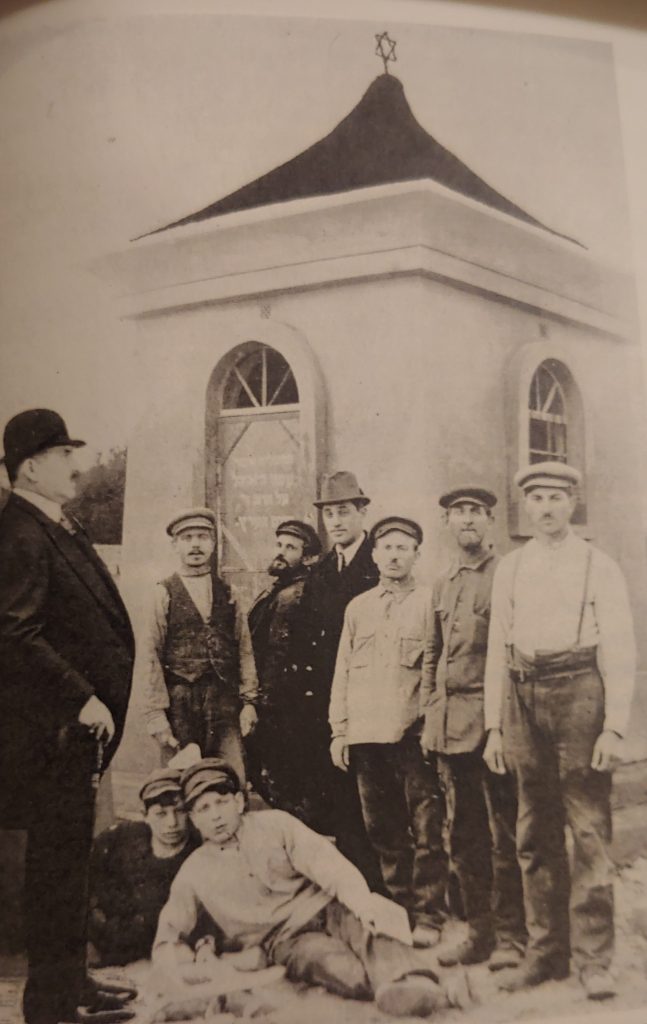

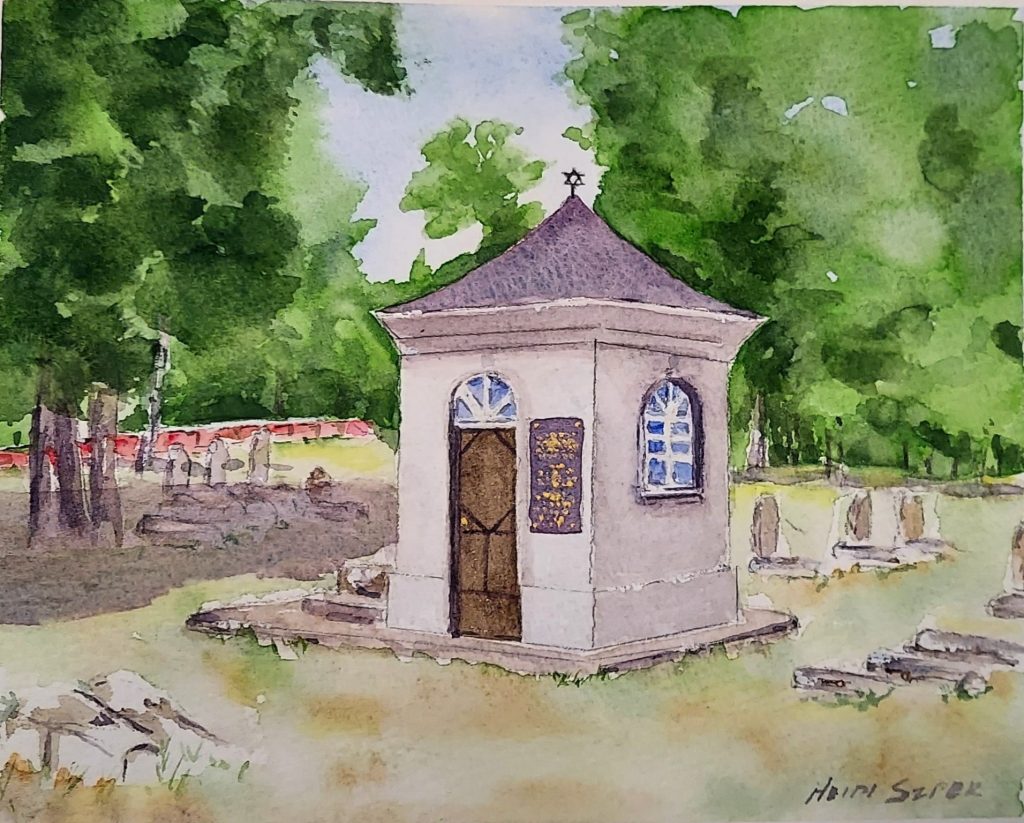

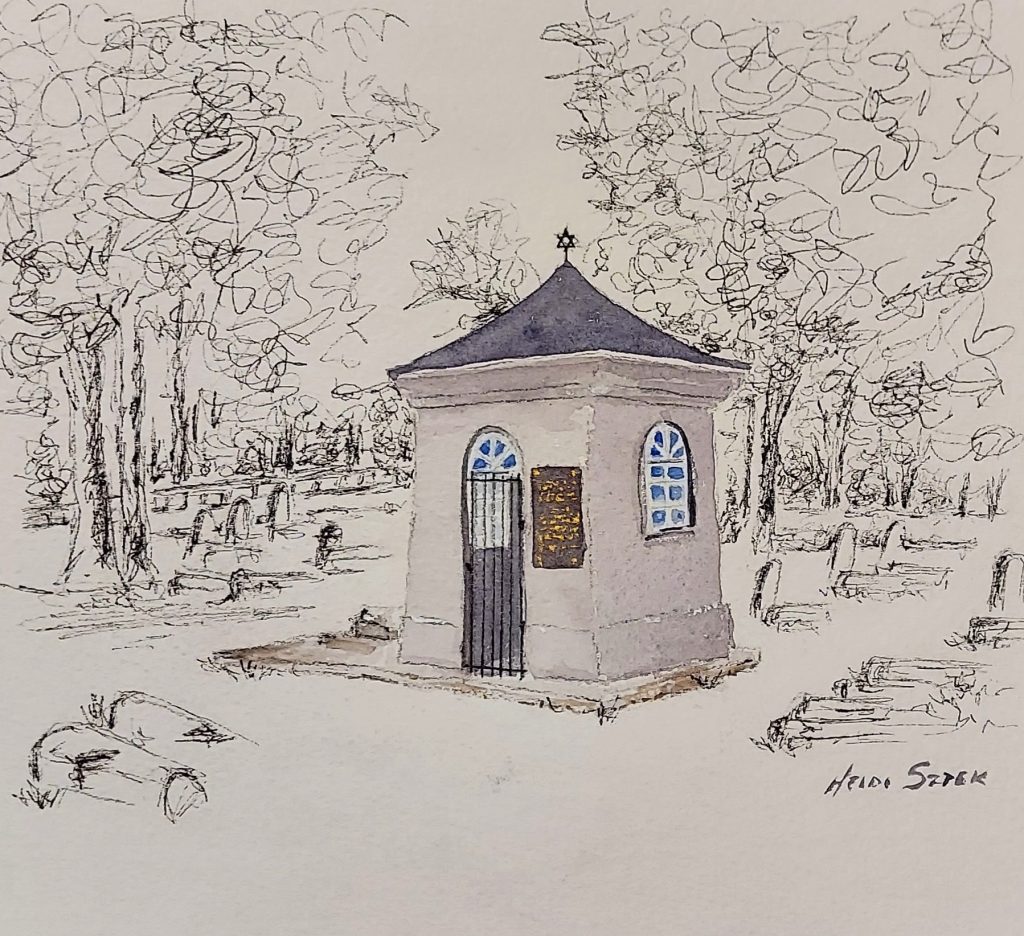

Today, on Bagnowka, the shell of an ohel for Bialystok’s Chief Rabbi Chaim Hertz Halpern (d. 1921) still stands. An historic photograph was captured not long after the ohel was erected in 1922 by the Bialystoker Center in New York. The details of its door, windows, and the dark roof, atop which stands a small wrought-iron Star of David, provide conservators with a clear goal for a complete restoration, envisioned in my watercolor below. The only divergent detail may be the granite plaque and inscription affixed in 2013 by the City of Bialystok (although another historic photo does preserve the plaque). The plaque now covers a simple inscription pressed into the concrete wall and the handwritten name on the original door. To restore the ohel to its near original appearance would not be a challenge. The concern, however, is for the safety of this structure on a non-functioning cemetery without frequent caretakers. A closed door and windows beg quizzical eyes. Another option as depicted in the ink and watercolor depiction below replaces the closed door with a wrought-iron gate; the windows could be constructed without panes.

Ink and watercolor, 2021. 5″ x 7″

Another ohel once stood on Bagnowka, that of Bialystok’s Chief Rabbi, Shmuel Mohilewer (d. 1898). He was also the rabbi who coordinated the establishment of this cemetery. Exactly when Mohilewer’s ohel was destroyed is unclear. It is visible in a 1943 Luftwaffe aerial photograph but not in a 1985 conservator’s photograph. In 1991, Mohilewer’s followers exhumed his remains for reburial in Israel, presumably to safeguard their teacher given the devastation of this cemetery. Photographs from their exhumation depict a front loader uplifting the foundation. Concrete pieces from this foundation were visible nearby as late as 2015. Today, only fragments of the ohel’s foundation and a depression in the earth provide clues to this gravesite. Given R. Mohilewer’s importance, especially as a founder of Religious Zionism, something should mark his former gravesite. Consider a symbolic ohel as depicted in the watercolor and ink painting below. Its form could mirror that of the Halpern ohel, with an affixed informational plaque that offers remembrance.

Watercolor and Ink, 2021. 7″ x 10″

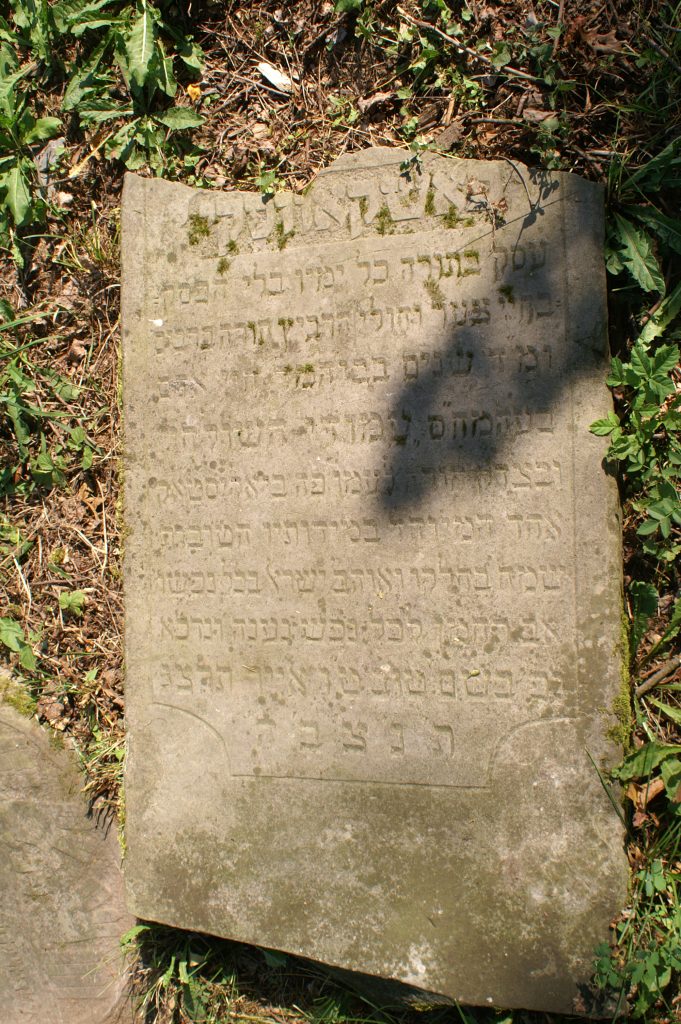

Not far from the former gravesite of Rabbi Mohilewer, once again stands a megalithic traditional Ashkenazi tombstone for the distinguished rabbi, scholar and author, Benjamin Isaiah Paszkowski (d. 1933). For years, only the bottom half of his matzevah peered from the earth near what we would learn was his gravesite. A chance search of the adjoining alley by volunteer photographer, Frank Idzikowski, in 2015, revealed that beneath the compact ground lay the top half. In 2019, the two parts were rejoined and reset on his gravesite by the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project. A chance visit by yeshivah students that same summer revealed just how significant Paszkowski’s theological writings were and still are today. It has long been known that traditional Ashkenazi sandstone matzevoth were once painted in white on black stain with, at times, a variety of colors highlighting the deceased’s name and the ornamental register. Re-staining and repainting a tombstone are challenging and expensive tasks. The art of watercolor shown here allows a visual of how this stone might once have looked while still preserving the knicks of its subsequent traumatic history.

Watercolor and Gouache, 2021. 7.5″ x 10″

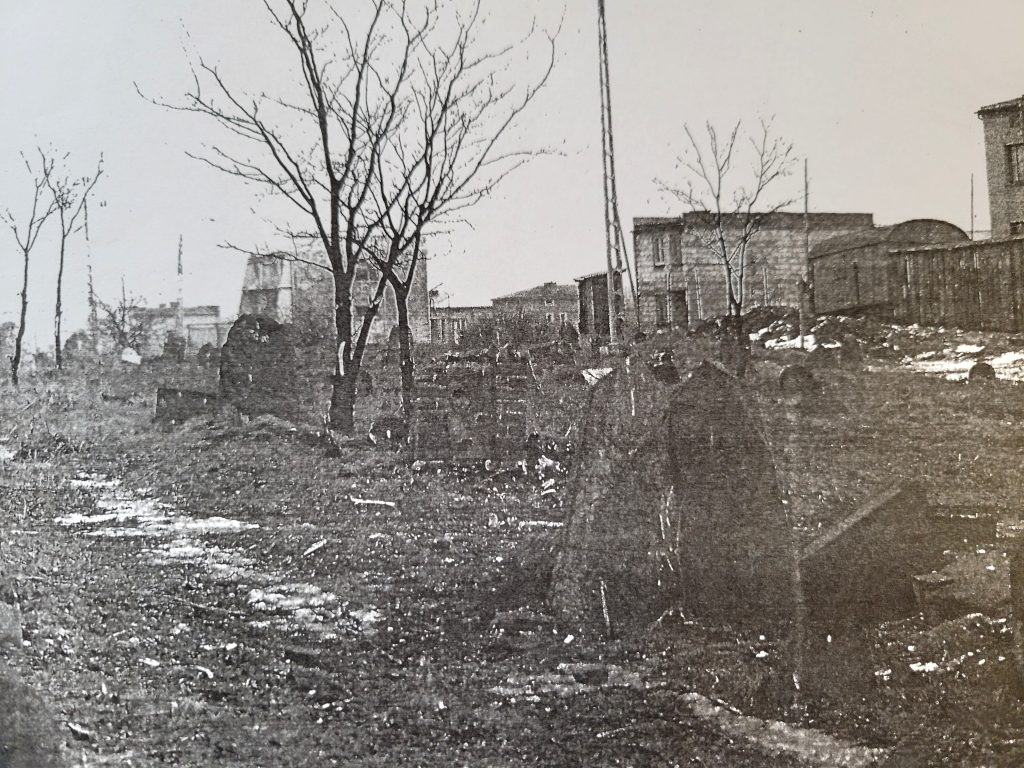

One of the most unique topographic features on Bagnowka cemetery is the large mound at left on entering. An approved test trench into this mound in c. 2012 revealed brick foundations for an extensive structure. Historic maps and WWII Luftwaffe aerial photos indicate that there was once a tripartite building that functioned as the burial house and caretaker’s cottage. The background (left) of an historic photo of the Memorial Pillar reveals this structure. Its three distinct windows, topped with white brick arches, are visible and match another historic post-WWII photo, captured from outside the cemetery. In the exterior cemetery photo, the height of the woman standing within one window’s ruins and the not-too distant main entrance reveal just how large and tall this structure once was. In a panoramic watercolor restoration, I attempted to recreate this structure. While the perspective is not perfect, the structure was impressive. Its windows (and a door) on both the interior and exterior walls would have potentially allowed a clear view of the cemetery from the street and the reverse as well. As one who has worked in and visited this cemetery since 2005, my eye struggles with the presence of such a structure, having only known the large tree which now shelters the mound. Such a painting, however, allows the viewer an opportunity to imagine the past and the future. If restored, this structure might serve as a small visitors’ center and museum. In this panorama, the pedestrian entrance is also restored. The interior cemetery wall functions as a non-intrusive lapidarium for the orphan fragments on this cemetery.

Watercolor, 2021. 5.5″ x 23.7″

In an earlier article (2007) on the aesthetics of Jewish tombstones, I engaged philosophy to consider the meaning of a tombstone, evoked by its shape, stone type, colors, even its relation to surrounding objects. Aesthetics as an avenue for meaning recently re-emerged for me amidst the physical act of painting. In a recent painting (below), an obelisk gently inclines against its presumed base. Fragments stand atop and beside this base. In the background, two simple boulder-style tombstones still stand in situ. A partial view of an undisturbed obelisk and its support bases can be seen at right. Obelisk and base both remember a Josef Becel, the obelisk in Hebrew, the base in Russian. The Russian preserves the year of death (1908), the Hebrew, his father’s name, Nahman, and short epithets. Together these two parts offer one biographical record, but also, they suggest more. In 1908, Tsarist Russia continued to control Bialystok; Russian language and culture infused Becel’s world. Hebrew, by contrast, emphasizes the Jewish religious tradition. The simple boulder tombstones remind us that this cemetery like the city of Bialystok began as a traditional Jewish world. Granite, especially the obelisk style, marked the modernity that would infuse this city c. 1921. As for the fragments on Becel’s gravesite, they offer a visual reminder of the devastation suffered once again under Russian dominance in post-World War II Communism. The occasional wildflower that grows on this cemetery is a reminder that nature reclaims what remains.

When art meets restoration, it can provoke contemplation about what once was and what can be. For me it also prompts contemplation about what should be preserved, conserved, or restored. If not restored, does a toppled tombstone respect the memory of a deceased? If restored, does restoration erase the traumatic history of an individual or a community? Perhaps conservation – preserving with only the most essential restoration, might be an alternative.

Consider one of the most provocative tombstone visuals I have encountered on Bagnowka, that of the adjacent tombstones of two Bloch cousins (d. 1898, 1904). On this cemetery, family members were not buried adjacent unless their deaths were in close temporal proximity. The Bloch cousins are separated by nearly six years. Yet, for some reason, that latter gravesite was still vacant until 1904. In a conservator’s photo from 1985, their adjacent tombstones gently incline together. In photos to the present, that visual bond perseveres. As our restoration progressed to the section in which they are buried, these two stones have been straightened just enough to assure their stability. Sometimes simple preservation is crucial.

And finally, consider one more time the ohel of Chief Rabbi Chaim Halpern partially restored since this photo capture in 2005. Perhaps this partial restoration is, respectfully, enough.

Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery, Bialystok, Poland, 2005.

for Rabbi Chaim Hertz Halpern, 2019.

Select References

Catalogue for Best Practices in Jewish Cemetery Restoration. Catalogue of Best Practices for Jewish Cemetery Preservation by ESJF – Issuu

1985 Conservators Report, Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery. Looking Back to Move Forward: Revisiting the 1985 Conservators’ Report on Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, Poland. – Jewish Epitaphs

Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project. (bialystokcemeteryrestoration.org)

Heidi M. Szpek, “And in their Death they were not Separated: Aesthetics of Jewish Tombstones in Eastern Europe.” The International Journal of the Humanities 5/4 (2007).

© Heidi M. Szpek, May 2022