Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D. Emerita Professor, Religious Studies, CWU/USA

I am an unintentional ‘keeper of the names’ (shomeret hash-shemot; שמרת השמות), a poetic title first bestowed upon me some years back by Amy Halpern Degen, one of the co-founders of the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project. The names are those found on the tombstones in Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery, the last extant Jewish cemetery in Bialystok, present-day Poland. The designation ‘keeper’ refers to my duties as the volunteer, who translates the Hebrew of the tombstones’ inscriptions and records names and vital data into a database. As for unintentional – that story begins about 15 years ago in southeastern Poland, in the tiny shtetl cemetery of Kolbuszowa.

In the Summer

of 2005, as an Assistant Professor of Western Religious Traditions, I travelled

throughout Poland, visiting Jewish heritage sites to further develop my

university courses on Jewish History and on the Holocaust. Inspired by the

memoir of Holocaust-survivor, Norman Salsitz (A Jewish Boyhood in Poland: Remembering

Kolbuszowa), I retraced the sites of his boyhood home, including the tiny,

abandoned cemetery on the outskirts of Kolbuszowa. There I witnessed the

graffiti and litter and weeds and ants of devastated and neglected Jewish

heritage.

But there I also encountered the exquisite beauty of the Jewish tombstone. Glittering in the mid-day sun, the finely chiseled letters of an acrostic poem preserved each letter of the deceased’s name painted in red, the remaining letters in black. Traces of a once whitish-blue background were also visible, all details evidence of the artistry accorded traditional Jewish tombstones. And I encountered Job. Job of the biblical text, that is, whose mournful but sapiential words, I would learn, were the most common epithet for men. I later wrote, “Can Ants Say Kaddish” for The Jewish Magazine online in reaction to this and other experiences in encountering Jewish heritage sites.

That trip also took me to Krakow, Oswiecim, Auschwitz, Lublin, Warsaw and dozens of small towns in between … and eventually to Bialystok. Destination Bialystok was not a common one in the academic world at that time. Yet I had wanted to incorporate a location off the beaten track in my course. By chance I came across a small volume, Jewish Bialystok and Surroundings in Eastern Poland, by then local historian and journalist Tomasz Wisniewski. The remnants of Jewish heritage, which he described, offered a unique view of Jewish life in the Podlasie region before the Holocaust. This trip took also me to the tiny town of Tykocin, once the seat of the Jewish kehillah (community) to which Bialystok belonged. In visiting its synagogue, rabbi’s house and the old Jewish cemetery, I connected with a rabbi guiding a youth group from abroad. Before leaving town, he directed us to a nearby bridge that stretched over the Narew River and asked us to look into its waters. Here, he said, were the tombstones that once marked the graves of Tykocin Jews. The story shocked the young visitors and puzzled me. I had neither heard nor read of it in Wisniewski’s book nor could I substantiate it with further research. On return home, I emailed Wisniewski regarding the accuracy of this narrative. He assured me that there were no stones in the Narew. And so ended our correspondence … until some months later. A random email appeared in my university mailbox with a polite request to translate a little Hebrew on a tombstone …

I had no inkling that, that trip would be the beginning of an almost yearly pilgrimage to Bialystok and Jewish heritage sites over the next 15 years, traveling as far north as Tallinn, Estonia and as far south as Budapest … nor could I have envisioned that, that Fall request to translate one Jewish tombstone would turn into a new direction in my academic career and in my life.

That email began the digital exchange of images and translations for the next five years, most images came from Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery in Bialystok, captured by Wisniewski, but others, too, came from cemeteries throughout Podlasie and various locals in Poland. At that time, I also contributed translations to JOWBR for cemeteries throughout Eastern and Central Europe. These images were typically captured by local photographers, as arranged by volunteers for JOWBR or www.jewishgen.org , and sent to me electronically by a JOWBR volunteer. These organizations were predominately interested in the vital details of the deceased as preserved in the Hebrew inscriptions on the tombstones. Thus, given and surnames, paternal and maternal names, dates of birth and death were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet, developed by these organizations. Such information might be the last extant record of their existence.

Vital details reclaimed with the lifting of the largest extant tombstone on Bagnowka of a Bialystok banker, Dov Aharon Khwoles, lifted by BCRP, 2016; and painted by ASF and now BCRP volunteer, Daniel Zamojduk, 2017.

As a scholar of Biblical languages and texts, trained by the Targumist (Aramaic specialist) Bernard Grossfeld (UW-Milwaukee) and the biblical Wisdom scholar, Michael V. Fox (UW-Madison), I recognized the use of biblical texts in Jewish tombstone inscriptions, their crafting of exquisite acrostic poems, poems in rhyme, admonitions, as well as historical details of the period hidden in epitaphic parlance. The exquisite Jewish sepulchral art, especially those styled as folk art, were a delight to the eye, enriching the epitaph of the deceased.

These translations became the inspiration of more than a dozen years of academic research, taking me on a new path in my academic career, from Targumic to Peshitta (Syriac) Studies centered on Job, to Women in the Bible, Religious Expression amidst Oppression, and finally to the Holocaust. Unjust suffering clearly was a key theme along with a delight in translation theory. Studying the Jewish epitaph, especially those from Bagnowka, touched on all these previous areas of focus. A selection of my writings can be found on my website.

“A blossom is fresh; a flower is tender. /

Before it has fully ripened, it was plucked off, it was killed…”,

mournful poetry, drawn from the biblical book of Job,

on the tombstone of a young girl, killed in the August 1920 Pogrom.

As a means to moderate the vast corpus of inscriptions and translations, I began a simple Excel database for the records gathered from Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery, modeled on those developed by JOWBR and Jewishgen with additional columns for the topics of particular interest to me: biblical verses, unique orthographic symbols, type of poetry, historical details, such as ancestral towns, publications by the decedent, and community roles and organizations, and death due to violence.

By 2007, the Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Database, first developed from digital images sent to me, also included photographs taken on site by my photographer – my husband, Frank Idzikowski of nearly 35 years. More accurately, when I write ‘I’ the person behind or better beside me in these travels is Frank. As a (now retired) Senior Adjudicator for the Veterans Administration and a military historian with a love of photography and travel, my research travels became an excellent opportunity to engage in what he also enjoyed as well as an opportunity to spend time together amidst hectic career schedules and the demands of parenthood. (Travels to distant lands and cemeteries can be quite peaceful!) Thus, he photographed many stones on Bagnowka and other cemeteries we visited in the Podlasie, as well as other venues in Poland and the Baltics. His photographs were used to document my 2007 Survey of the Jewish Cemeteries in the Grodno Gubernia of Poland, published to the BialyGen webpage, coordinated by Mark Halpern, another key player in preservation of Jewish Bialystok’s heritage. Frank quickly learned best photography practices for tombstones – best time of day, the basic structure of an epitaph to ensure all vital details were captured, the occasional use of chalk or earth to illuminate a barely legible inscription. As much as documenting on site is best, these images allowed me to review and the record the vital details of each inscription and appreciate epigraphic and literary details accorded each person.

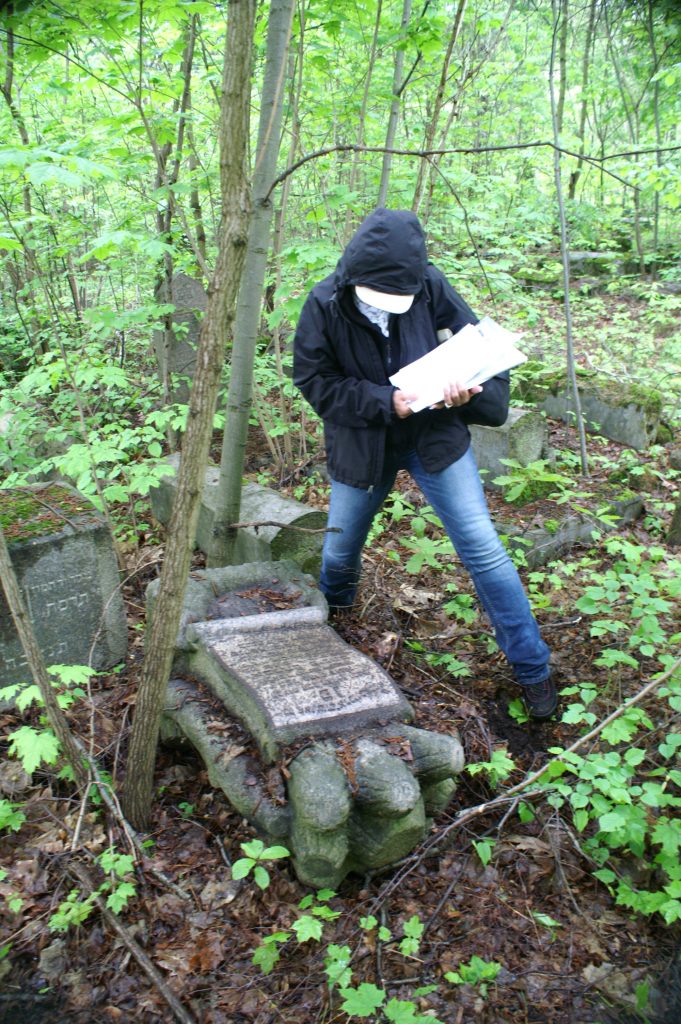

Heidi Szpek checking vital details, 2006.

Being a keeper of the names is also a story of contemporary names. Though the task of translating is a solitary one, it is enriched by occasional and persistent folks whose paths cross mine in the intentional quest of preserving memory. In 2009, by chance I met Bialystok’s local Jewish representative and president of Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej Polska-Izrael w Bialymstoku, Lucy Lisowska, and learned of her efforts, assisted by Waldemar Mierzejewski and a community of local volunteers, in restoring Bagnowka Cemetery. She also coordinated efforts with the German-based organization ASF (Aktion Süchnezeichen Friedensdienste)that brought an international group of volunteers to learn of Jewish heritage in Bialystok while cleaning and engaging in restoration. In a two-week Summercamp, using a tripod and pulley system and brute strength, they reset, cleaned and painted tombstones in sections immediately on entering the cemetery and in the Memorial Complex under my direction in 2014. Having worked side by side with these volunteers for many seasons, I’ve had the honor of meeting folks from Germany, Israel, Poland, Belarus and Ukraine.

A chance visit to the cemetery in 2015 by Amy Halpern Degen (MA), on a heritage tour, and her husband Josh Degen, a stone mason, brought new names to this cemetery project and opened the most recent chapter in Bagnowka’s restoration and the documentation of its stones. Joined by long-time MA friends, Howie and Paula Flagler, the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Projectwas founded. Its goal is to restore the dignity of the last Jewish cemetery in Bialystok and reunite, whenever possible, Jews worldwide with their ancestors, who were laid to rest on this cemetery. Mechanized equipment now replaced the hand-pulley labor-intensive strategy. Where once a two-week Summercamp saw the reset and care for about 25-40 stones, three years under the BCRP has raised nearly 1000 stones. These efforts have definitely impacted the database, pushing the pre-2016 total of entries from about 2300 to nearly 3300.

Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Project volunteers, Summercamp 2018.

This increase has prompted me to systematically revisit the database, reviewing and comparing images captured by Wisniewski, my husband and myself from pre-2006 to the present. Many of the earlier photos capture tombstones who inscriptions are partially obscured by soil, grasses and general detritus. Thus, vital details were not visible. As new stones are now uncovered and complete sections are restored, updated data can also be added in addition to new entries.

As I revisit this database, with eyes ten-years more seasoned than at its first production, new questions also emerge with directions for future research and restoration. For example, more and more inscriptions record that the deceased was a merchant. Bialystok was known for its lumber and textile industries, in-town markets with merchants but also those who traversed eastward as far as possibly Odessa and Taganrog. Their travels were first by horse and wagon and then by train with its arrival in the early 19th century. More than once, extant inscriptions record that a merchant’s death was precipitated by random violence, including murder while on the road. To write a history of Bialystok’s Jewish merchants, inspired by their epitaphs, might be a fascinating approach! As for Job and the epitaphic poetry that first caught my eye, that topic, too, is worthy of a volume, Jewish Poesia (Polish for poetry) in Podlasie and Beyond. The poetry on the Bagnowka stones is far more extensive than on stones in other cemeteries in this region. But Bagnowka is not only part of the Podlasie region; first it belonged to the Grodno Gubernia, an administrative designation established in the late 18th century. As I’ve already demonstrated in earlier publications, literary and artistic parallels for Bagnowka extend eastward to Belarus and northwestern Ukraine. I’m thinking it’s time for a road trip for Frank and I! This time, east to explore other cemeteries in the Grodno Gubernia. I would relish the opportunities to examine the stones stacked in the Brest fortress in Ukraine. My book, Bagnowka: A Modern Jewish Cemetery on the Russian Pale though just released in 2017 will be soon needing a revision, given restoration efforts these last three years. That will be in the works as well as a Polish translation.

Revisiting the database also provokes questions regarding restoration. For example, if over 5000 Bialystok Jews died of hunger between 1915 and 1920 during and immediately after WWI (Sara Bender, Jewish Bialystok, 18) why doesn’t the epitaphic record reflect this loss? Will stones still concealed beneath over 70 years of detritus support this statistic? And again, in sections still covered by young growth woods, database images reveal a proportionally larger amount of the stones broken in half, often with the bottom portion still in situ. The top of these stones were quite likely used for construction projects in the nearer environs of this cemetery and Bialystok. Perhaps these stones can anonymously be returned to the cemetery. I’ve seen this incredible community support in Marla and Jay Osborne’s Rohatyn Jewish Cemetery Project in Ukraine . Tops could be married with bottoms, reclaiming both the vital data from these stones, as well as restoring dignity to the gravesites and to Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery.

My role as ‘keeper of the names’ could just as easily be rendered ‘guardian of the names’ as the Hebrew shomeret, at its base, means “to keep, guard.” Regardless of whether I keep or guard, the names and vital details are not kept for my own edification; my research, at times, may seem that way. Rather these names are for all interested, with records disseminated to JOWBR, Jewishgen.org and anyone seeking ancestral connections. Moreover, the gathering and preserving of these names relies on a network of other names (folks), only a handful of which are mentioned in my words above. This process of returning names to the historic record, indeed to humanity, depends on all who participate in this restoration. The names we restore mark individual identity, but their restoration also mends the threads of memory, uniting past and present. This reunion becomes a fulfillment of those final words of blessing on nearly every Jewish tombstone: “May one’s soul be bound in the bond of eternal life.”