by Heidi M. Szpek, Ph.D.

Emerita Professor, Translator, Historian, Board Member,

Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Fund

1. Bagnowka was NOT devastated by the Nazis in World War II. In particular, no Nazi battalion drove through the cemetery wreaking havoc. The recent acquisition of Luftwaffe aerial photos in conjunction with local lore and the 1985 Conservators Report confirms that this cemetery was systematically vandalized and dismantled post World War Two.

2. NO tombstones on Bagnowka predate the establishment of the cemetery. Bagnowka was established on the cusp of 1891- 1892. The 1985 Bialystok Conservators Report erroneously reported that tombstones dating to 1874 and 1876 were extant on the cemetery, possibly reburied from another location once Bagnowka was open. The Hebrew letter Nun (=50) was misread as Lamedh (30) or given the wrong numerical equivalent. The tombstones references are extant today with the proper dates of 1894 and 1896!

3. The black Memorial Pillar that commemorates the 1906 program in Bialystok and two 1905 massacres is not currently in its original position. Luftwaffe aerial photos, the Conservators 1985 Report and articles in the Bialystoker Stimme magazine revealed that the pillar was toppled in 1981. In 1985, the New York Bialystoker Home restored three of its four pieces in a section just SW of its original location, which was too devastated to support this monument.

4. A second ohel (rabbi’s hut) once stood on Bagnowka just one section north of the extant ohel of Rabbi Chaim Hertz Halpern (d. 1921), as confirmed by Luftwaffe aerial photos, the Bialystoker Stimme (1992) and referenced in A.S. Herzberg’s Pinkos Bialystok. This second ohel marked the gravesite of none other than Chief Rabbi of Bialystok, Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever (d. 1883-1898), who was responsible for establishing Bagnowka Beth Olam.

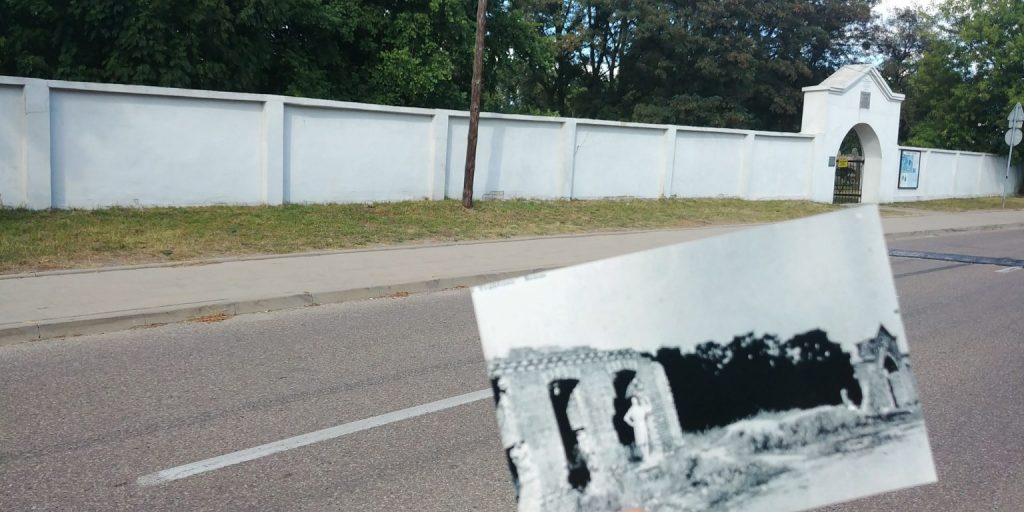

5. Bagnowka originally had a caretaker’s cottage and an adjoining burial cottage on entering the main entrance on Ul. Wschodnia. These structures are confirmed by Luftwaffe Aerial photos. These structures were dismantled by the local population in the early post-War years for use in ovens.

6. The western wall of Bagnowka originally adjoined UL. CMENTARNA, which led to the Catholic Cemetery. This street also held another substantial entrance to Bagnowka. Aerial photography and the Conservators Report confirm this street and entrance. This additional entrance may explain the absence of burials within adjoining sections.

7. The most easterly sections of Bagnowka were originally reserve lands, meaning lands held for future burials. Aerial photography, the Conservatives report and a 1937 cemetery map confirm these sections were never utilized for burial.

8. Bagnowka Cemetery was not originally located within the city of Bialystok. Per Tsarist legislation in the 19th Century, cemeteries were no longer permitted within the living community for hygienic reasons. Bagnowka was thus established outside the city limits near the small town of Bagnowka where Catholic, Russian Orthodox and Lutheran cemeteries were already established.

9. The first burial on Bagnowka was that of Fruma, daughter of Reb Yehuda Leib. She died on Monday 2nd Tevet year 5652 [21 December 1891] and was buried on the same day the cemetery was dedicated. Oral tradition reports that the last burial was that of a doctor in 1969 in a NW section of the cemetery. Neither burial sites have yet been located. Today, the oldest extant matzevah is that of Ita Riba, daughter of R. Tsvi Ari. She died on 8 Tevet 5652 [27 Dec 1891] just six days after the cemetery’s opening! Today, the most recent matzevah mark the gravesite of Tsvia Halpern in 1952. This update just occurred during the 2022 Workshop on Bagnowka!

10. Comparative research on the symbols used on Bagnowka has revealed that artisan improvisations of the Lion of Judah find parallels as far West as Warsaw and as far east as the regional town of Narewka and Swieta Wola (current-day Belarus). Such affinity reveals that the Bialystok artisan tradition was part of a much greater artisan community.

11. The largest monument on Bagnowka is the megalithic monument of the bank director Dawid Chwoles (d. 1906), which stands in Section 1 just inside the main entrance. After decades lying face down in the earth, this tombstone was re-erected in 2016. Using a small backhoe, a crew of five men from the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Fund re-erected this monument to its original place. It stands at over seven-feet high and weighs almost 1.5 tons. Its inscription was restored by Daniel Zamojduk, the tallest volunteer, in 2017!

12. The smallest matzevah, affectionately called the ‘Ali’, was named for volunteer Ali Flagler (2017) whose persistence revealed that what was once thought to be a structural component of a tombstone is rather a tombstone with a painted inscription. No other ‘Ali’ stone, at present, reveals such an extensive inscription. The final count of ‘Ali stones has yet to be completed, pending further restoration but, once completed, will necessitate revising the number of extant tombstones!

13. At present, nearly 3500 tombstones have been documented by Dr. Heidi M. Szpek. This data is available at: Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Burial Registry – Jewish Epitaphs. Aerial photography as well as site surveys suggest that as many as 2500 more tombstones could be extant. The combined total of 6000 would parallel that provided by Dr. Tomasz Wisniewski in The US preservation report of Jewish Heritage in Poland “Survey of Historic Jewish Monuments in Poland” by Samuel D. Gruber (syr.edu) . The first substantial documentation project was initiated by Dr. Wisniewski in 1999 with translations by Dr. Heidi M. Szpek and Sara Mages (available at: Dokumentacja cmentarza żydowskiego Bagnówka – Społeczne Muzeum Żydów Białegostoku i regionu (jewishbialystok.pl) and www.bagnowka.pl) This data has also been shared with JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry.

14. Bagnowka began as a traditional Jewish cemetery but was transformed into a modern Jewish cemetery where both traditional and modern funerary elements – tombstone style, sacred and vernacular languages, epitaphic and artistic traditions, stood side by side throughout its history (1892-1969). In burial patterns, in particular, we see an attempt to ameliorate the modern with the traditional as gender distinction is maintained NOT by section but row by row.

15. Not all inscriptions on Bagnowka were painted in gold or gold-leaf. The traditional Ashkenazi tombstones held white inscriptions against a black background; their symbols were frequently painted in bright colors. Today, it is not uncommon to find these white/black tombstones and more and more often remnants of bright colors are discovered.

16. The first clean-up effort of Bagnowka was organized by local Bialystok resident Miroslaw Szut in the 1990s, bringing volunteers from the Netherlands.

17. Since the early 2000s, cleanup efforts on Bagnowka were initiated and maintained through Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej Polska-Izrael, coordinated by its president and local representative to the Warsaw Jewish Community, Lucy Lisowska, often with the assistance of local school children.

18. Repair to the cemetery walls was funded by Bialystok child Holocaust survivor, Sam Solasz, z”l, coordinated by Centrum’s Lucy Lisowska.

18. From 2010 to 2015, and 2017-2018, Aktion Suhnezeichen Friedensdienste (ASF) held eight summer camps devoted to restoration, coordinated by Centrum’s Lucy Lisowska. ASF raised over 100 matzevoth by hand or with the labor-intensive tripod, designed by their first Summercamp leader, Dr. Andreas Kahrs of Berlin. This tripod machine was replicated and improved by Bialystok, long-time volunteer Waldemar Mierzejewski.

18. In 2016, the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Fund held its first Summercamp on Bagnowka, implementing the use of mechanized equipment to assist in lifting tombstones. Since 2016, over 1400 tombstones have been reset; hundreds of tombstones have been cleaned and repainted; five families have been reunited to their ancestors on cemetery; and hundreds of new vital details have been contributed to the historical record. The BCRF was established in 2016 by Bialystoker Amy Degen and her husband, Josh Degen, along with their friends Paula and Howie Flagler of Massachusetts!

19. In 2019, after formal on-cemetery review by Filip Szczepański, representative of the Rabbinic Commission of Cemeteries in Poland, the BCRF received formal rabbinic sanction from the Office of the Chief Rabbi of Poland, Michael Schudrich, for its restoration methodology.

20. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, work on Bagnowka did continue! In the Fall of 2020, The Association of the Museum of Jews of Bialystok, coordinated by its president, Andrzej Rusewicz, cleared sections in the NW of the cemetery in preparation for 2021 restoration efforts. And Centrum’s Lucy Lisowska continued cleanup efforts with local school children.

21. Restoration efforts for 2021 are currently underway by the Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Fund!! Stay tuned!!

For specific articles see:

Heidi M. Szpek, The ‘Rediscovery’ of the Ohel of Rav Shmuel Mohilever on Bagnowka Cemetery, Bialystok, Poland. – Jewish Epitaphs

Heidi M. Szpek, Conservators Report 1985: Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery, Bialystok, Poland – Jewish Epitaphs

Heidi M. Szpek, Bagnowka-Cemetery-Guidebook-English.pdf (jewishepitaphs.org).

Heidi M. Szpek, Report: 2017 Białystok Jewish Cemetery Restoration Project – Jewish Heritage Europe (jewish-heritage-europe.eu)

Heidi M. Szpek, Bagnowka: A Modern Jewish Cemetery on the Russian Pale (iUniverse, 2017).

For more information on these 21 topics (and more) visit:

Heidi M. Szpek, Jewish Epitaphs – www.jewishepitaphs.org

Bialystok Cemetery Restoration Fund – www.bialystokcemeteryrestoration.org

Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej Polska-Izrael www.bialystok.jewish.org.pl

Społeczne Muzeum Żydów Białegostoku i region www.jewishbialystok.pl